My Life with Rabin

on Eight Oil Lamps and Eight Incandescent Lamps, 1992

(View the painting)

There is in our house another house. It is a big hut, represented in a monumental painting by Oscar Rabin that measures 114 x 195 cm, is dated 1992, and bears the strange title “Eight Oil Lamps and Eight Incandescent Lamps.” This bewitching painting, which has been part of our life for many years now, featured in a solo exhibition by Oscar Rabin organised at the Le Monde de l’Art gallery, also in 1992. The artist had been living in France for fourteen years when he painted this picture, and he had to wait another sixteen before he could go back to Moscow, after thirty years away. One day, this emblematic canvas came into our home, accompanied by its new owner, Marc Ivasilevitch. The whole family took to it at once, quite spontaneously.

I live in a daily dialogue with this enigmatic work. It was this painting that made us want to meet its maker. And our professional life changed as a result. We acquired other works by Oscar Rabin, which now constitute the basis for a complete exhibition.

It may be that for me this whole story began much earlier, with studying Russian at school, then a trip to Moscow and Leningrad, meetings with dissidents and, finally, a marriage. If none of this had happened, I certainly would not have felt so moved by the Russian, very Russian world of Oscar Rabin.

Evgeny Barabanov and Barbara Thiemann, two eminent art historians, have written remarkable critical texts on Rabin’s paintings, notably on the occasion of his major exhibitions in Moscow, at the Pushkin Museum in 2007 and at the State Tretyakov Gallery in 2008. I shall not try to match them. Rather, I would like to try to share my own experience, starting with this picture that I know so well. It is a risky endeavour to undertake such a confrontation, between narration and interpretation, for I want to avoid lapsing into a mode of pathos or quaintness that are quite alien to Rabin’s pictorial expression.

What do we see? A dark, isolated hut, its walls lopsided, almost in ruins, spreads out in the snow, in greyish light, in the middle of a waste ground, seemingly poor, humble and dilapidated.

What we can recognise here is the artist’s own home, that concrete hut twenty metres square in Lianozovo where he lived with his wife Valentina Kropivnitskaia, herself also a painter, and their two children, Katia and Alexander, between 1951 and 1965. Lianozovo was a suburb of Moscow. Its name was later given to the group of nonconformist artists who gathered there around Oscar Rabin. When Stalin died, in 1953, taking advantage of the short “thaw” authorised by Khrushchev, Rabin and Kropivnitskaia began to receive poets and artists such as Genrikh Sapguir, Igor Kholin, Lev Kropivnitsky, Vsevolod Nekrassov, Kolya Vechtomov, Volodya Nemukhin and Lidia Masterkova. Since it was impossible to exhibit their paintings in official venues or galleries, they displayed them at home – in “apartment exhibitions” as the expression went at the time – for Russian and foreign art lovers.

It has sometimes has been said that Rabin’s hut is reminiscent of Chagall’s beloved shtetl. But the tender Surrealist dreams of the Jewish painter are totally absent from Rabin’s representations. Like the Soviet identity card, the modest little concrete house in Lianozovo is an iconic presence in his work. The realist painter of a reality that the Soviet regime could not tolerate, Rabin focused his dissidence around these two images. Stripped of Soviet nationality in 1978, the same year as Rostropovich, and forced into exile in France (before actively adopting the country), the artist was always putting forward this piece of land, on the one hand, and his identity card, on the other.

He thus bestows a dark beauty on this hut that embodies memory and time, which covers a large part of the canvas, at first adorning it with an almost tactile material that is his almost instantly identifiable artistic hallmark. At first glance, all we see there is a geographical map in relief, with ridges and crevasses formed by rough impasto. But it is on this first abstract plane that Rabin organises the real, the architecture of his memories of Russia, which blend with those of France.

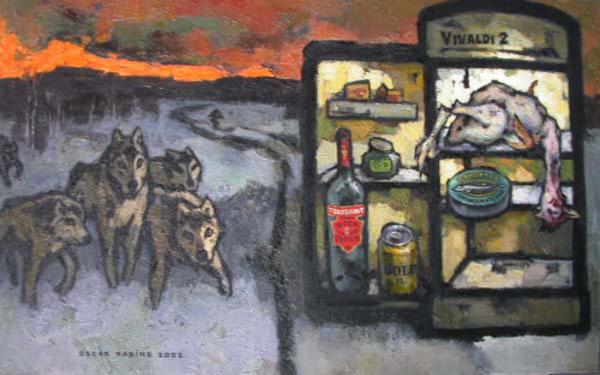

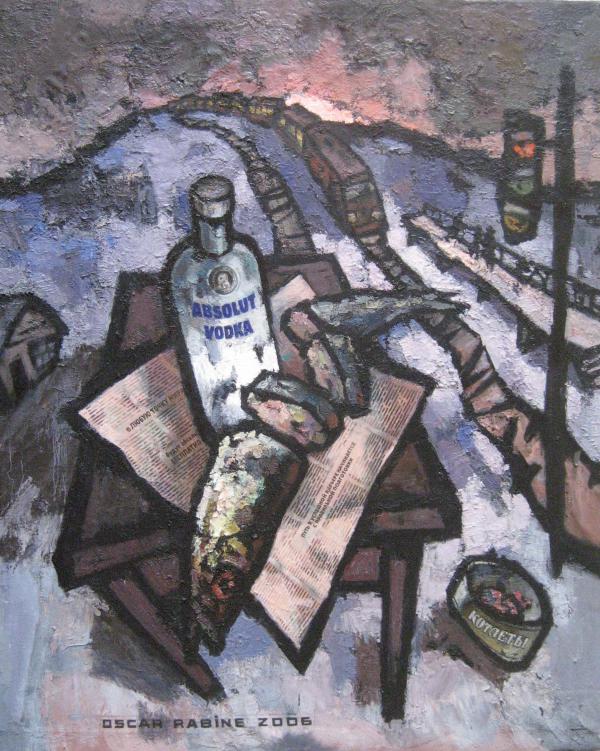

Even today, I still wonder about that grey, luminous matter. Sometimes, when he is absorbed in his painting and has forgotten all about me, I sneak a look at his work table. I try to discover the secrets of his art. I study the palette and the mass of oil covering it. The little mounds of white and black paint are much bigger than the other colours. I love the old tin pot and its homely smell of turpentine. Like some archaeological object, it has accompanied Rabin’s work ever since Lianozovo. Brushes old and new stand like a bouquet in a jar. I smile at his obsessions: herrings, the bottle of vodka, the little car or the miniature Eiffel Tower that he uses as a model. When Valentina was still alive, my curiosity about specific dates, about the events behind his paintings, and of course, the secret of his materials, was boundless. “How does he do it?” I asked. And she would always answer with a conspiratorial whisper, gesturing as she spoke, as if she were sweeping the table with one hand so as to gather up an imaginary fistful of dust to mix with the oil. It is in this deep substance, this mixture of oil, earth, dust, sawdust and sand, in muted, matt colours, that Rabin grounds and confronts his world. Like Antaeus recovering his strength when he touched the earth, he draws physical and mental energy from intimate contact with the earth of Lianozovo, which has now became paint. I let my gaze wander over the canvas. This invocation of the earth reassures me. It reminds me of that “right to stand foursquare on the soil” claimed by Leon Tolstoy when he ploughed the land of Yasnaia Polania with his muzhiks. The monumental format of the painting is underscored by a palette limited to earthy colours, with winter greys warmed by autumn browns. Particles of white glazes, nacreous and luminous like snow, lighten the density of the matter.

The hut asserts its presence in the space of the painting by the play of vertical and horizontal slats of wood glued to the canvas, which punctuate the equilibrium of this confused mass of wood, oil and glued paper. These disruptive wooden elements, which in a sense contradict – or, on the contrary, heighten – the image, form a cross. Since Rabin did not claim to be a believer, this sign should probably not be taken to indicate a return to the true faith. But this Orthodox cross filling our view does undeniably introducer a kind of distance, one that is both magical and concrete, between the hut and the viewer. It is as if the memory were tinged with the sacred. At the centre of this seeming disorder, through narrow windows we see the tiny heads of Rabin and his family. They are huddling together, as if for protection against the everyday dangers of the outside world. From this house where they seem to have taken refuge, they all look straight out at a horizon that is blocked and yet not without hope.

In The Tale of Tales (1978), which was voted best animation film of all time in 1984, Yuri Norstein evokes the old house in the Maryina Roshcha district of Moscow where he spent twenty-five years of his life. He evokes the noise of the rain in the evening, and the dust, and the traditional lullaby heard in the house next-door. The house is no longer there. It has been replaced by a sixteen-storey block of flats. The screech of tyres and yelling of horns have replaced the lullaby. Only the little wolf, Norstein’s childhood hero, still inhabits the house and its yard. Oscar Rabin conjures up a similar nostalgia for that lost world where we once lived. In the background of his painting, to the left, he too depicts the threatening growth of concrete buildings. Represented in the form of white grids, these smooth, tall expanses look totally dehumanised. The people in the wretched hut look as sad as the world around them, which is cruelly lacking in prospects, both literal and figurative.

However, the dramatic tension of this crepuscular scene is offset by the light that shines from the three oil lamps. If the other three incandescent lamps, receding into the distance at the top of the painting, are unlit, like an aborted modernity, then these other ones bring the message of faith in the present. More than the cross, it is these lights in the darkness that endow the painting with its undeniable spiritual dimension. As the only elements taken from the intimate world of the hut, here they are theatricalised by the painter’s gaze, as if put on stage outside it, like an allegory. Their diffuse, gentle light is like the glow of candles or moonlight, as seen in other works by Rabin. These flames devoid of violence impart an upwards movement to the hut. They seem to denote a desire for knowledge and openness. Their flame is like a feeling of attention to others. The nonconformist painter Rabin is a believer without a chapel, a man of religion without a dogma.

On the roof of the hut the word ROSSIA is written in the style of the Constructivist painters, who used letters simply for their plastic qualities. An artist of the post-war years, Rabin reconciles contraries within a fully accepted modernism. His realism, which is sometimes close to the painting of Ilya Repin, veers into hallucinatory, expressionistic twists worthy of Eisenstein. And his monochrome collages draw on the synthetic Cubism created using newsprint by Picasso, and on the Russian Futurists, as much as they do on the geometrical forms of iconic Suprematism championed by Malevich. As for the six letters, they should no doubt be read as a hidden signature. ROSSIA is the hut, and the hut is the House of RUSSIA, and RABIN is RUSSIA in exile. This hovel was part of a labour camp. Common law prisoners, whom Rabin was supposed to direct, worked there building a railroad. There were huts like this one in labour camps like that all over Soviet territory. This hut is not the shtetl in Vitebsk, it is life in the Soviet Union in general.

“Pictorial space is a wall, but all birds in the world fly freely there at every depth,” said Nicolas de Stael. For me, Oscar Rabin’s uprooted hut, floating weightlessly over the flames of eight oil lamps, is like a big, free bird, hovering over the torments of history. Its tiny, yellowed inhabitants seem to be struggling with their destiny, between the loss of the past and a thirst for the future. The particular beauty of this painting pitched between nostalgia and hope is further heightened by that feeling of loss: the loss of this moment and this place. Three moments are superimposed here, in a gradual, movement of time that has something contemplative about it: the harshness of the 1950s, the way they were remembered in 1992, and the vision we have of the whole period today, in 2010. Memory holds back recollections, smells and images, it holds back time and makes the private moment immortal. It is this pitiful miracle, accomplished by memory, that makes Rabin’s work as eternal as it is ephemeral, and for me, every bit as moving as it was on the very first day.

Michèle Hayem Ivasilevitch, February 2010

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2012

Galerie Vieceli, Cannes, France

2009

Gallery Mimi Fertz - New-York - USA

2008

"Oscar Rabine Three Lives" The Tretyakov, exhibition timed to the 80th anniversary since the birth of the classic of Soviet non-conformist art.

Oscar Rabin, Musée d'art et d'archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux, France

2007

Oscar Rabin, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

2004

A&C-Projects, Peter Nahum At The Leicester Galleries, London

2001

Mimi-Ferzt Gallery, New York

A&C Projects, Eric de Montbel Gallery, Paris

1998

Mimi-Ferzt Gallery, New York

1996

Esch Theatre Gallery, Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

Cultural Club of European Institutes, Luxembourg

1993

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

1992

Le Monde de l'Art Gallery, Paris

1991

Museum of Literature, Moscow

Marie-Thérèse Cochin Gallery, Paris

1986

Eduard Nakhamkin Gallery, New York

1985

Miro-Spizman, London

Holts-Halversens Gallery, Oslo

1984

Museum of Modern Russian Art, New Jersey

Marie-Thérèse Cochin Gallery, Paris

1983

Steink Gallery, Vienna

1982

Holts Halversens Gallery, Oslo

1981

Chantepierre Gallery, Aubonne, Switzerland

1977

Jacquester, Paris

1965

Grosvenor Gallery, London

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

1957

Sixth World Festival of Youth and Students, Moscow

1964

Aspects of Contemporary Soviet Art. Grosvenor Gallery, London

1965

Grosvenor Gallery, London. Solo Exhibition

The Fielding Collection of Russian Art. Arleigh Gallery, San Francisco

1966

Sixteen Moscow Painters. Nineteenth Festival of Fine Arts, Sopot-Poznan, Poland

1967

Chausée Entuziastov. Druzhba Club, Moscow

Paintings and Drawing, A. Glezer Collection. Georgian Artists' Union, Tbilisi, USSR

Sixty Years of Russian Art. Vincent Price Gallery, Chicago

Fifteen Young Moscow Painters. Galleria il Segno, Rome

A Survey of Russian Painting, Fifteenth Century to the Present. Gallery of Modern Art, New York

New Paintings from the USSR. Galerie Maison de la Tour, St-Restitut, Drôme, France

1969

The New School of Moscow. Galleria Pananti, Florence

Institute of World Economics and International Relations, Moscow

The New School of Moscow. Galerie Interior, Frankfurt, Galerie Behr, Stuttgart, West Germany

1970

New Tendencies in Moscow. Museo Belle Arti, Lugano, Switzerland

Alexei Smirnov and the Russian Avant-Garde from Moscow. Kunstgalerie Villa Egli-Keller, Zurich, Switzerland

1971

Ten Artists from Moscow. Køobenhavns Kommunes Kulturfond, Copenhagen, Denmark

1973

The Russian Avant-Garde: Moscow. Galerie Dina Vierny, Paris

1974

Progressive Tendencies in Moscow 1957-70. Bochum Museum, West Germany

Eight Painters from Moscow. Musée de Peinture et de Sculpture, Grenoble, France

Autumn Open-air Exhibition. Cheremushki, Izmailovsky Park, Moscow

1975

Twenty Moscow Artists. Bee-keeping Pavilion of the Exhibition of Economic Achievements, Moscow

Russian Nonconformist Artists. Kunstverein, Braunschweig, Freiburg, West Berlin, West Germany

1976

Russian Museum in Exile, Montgeron, France

Russian Nonconformist Artists. Kunstverein, Konstanz, Saulgau, West Germany

The Religious Movement in the USSR. Parkway Focus Gallery, London

Alternatives. Kunstverein, Esslingen, West Germany

1977

Galerie Jaquester, Paris. Solo Exhibition

Unofficial Russian Art from the Soviet Union. Institute of Contemporary Arts, London; with the collaboration of Russian Museum in Exile, Montgeron

New Soviet Art. La Biennale de Venezia. Venice

1978

New Art from the Soviet Union. The Arts Club of Washington, Washington DC, Kiplinger Editors Building, New York, The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, New York

Russian Unofficial Art. Musée du Vieux Chateau, Laval, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tours, France Seven Artists from Russia. Galerie Campo, Antwerp, Belgium

New Russian Art. La Biennale di Bellinzona, Bellinzona, Switzerland

Ten from Russia. Galerie Hardy, Paris

New Soviet Art. La Biennale de Turin, Turin, Italy

XXVI Salon Art Sacre. Musée du Luxembourg, Paris

Ten Russian Dissidents. Kunstamt Charlottenburg, Berlin

Modern Unofficial Soviet Art. Municipal Museum, Tokyo

1979

Moscow-Paris Exhibition. Museum of Contemporary Russian Art, Montgeron, France Russians in Paris. Galerie Bellint, Paris

XIIIth Salon of Mayenne, Mayenne, France

Contemporary Russian Art. Galerie Moscou-Petersbourg, Paris

Fifteen from Russia. Galerie Virus, Lausanne, Switzerland; with the collaboration of Galerie Moscou-Petersbourg, Paris

Moscow-Paris Exhibition, Galerie Katia Granoff, Paris; with the collaboration of Galerie Moscou-Petersbourg, Paris

XXVIIth Salon of Sacred Art, Paris

Four Russian Artists. Galerie Berau, Ühlingen-Berau, West Germany

The World Through the Eyes of Russians. Galerie Moscou Petersbourg, Paris

l'ere quadriennale d'art contemporain. Maison Dorée de Lyon, France

1980

Premiere Biennale des peintres Russes. Centre des Arts et Lousirs du Vesine, France Seventy-Five Years of Russian Painting in Paris. Galerie Chantepierre, Aubonne, Switzerland Fifteen from Russia. Galerie Moscou-Petersbourg, Paris

Biennale de l'Art Graphique-80. Galerie Moscou-Petersbourg, Paris

Nonconformist Russian Art. Exposition Galleries, Vancouver, Canada

Russian Painters at Villandry. Chateau de Villandry, France

Exhibit of Unofficial Russian Art. Salone Fieristico, Rimini, Italy

Unofficial Soviet Artists. Galerie Holst Halvorsesns Kunsthandel A. S., Oslo, Norway

1980-81

Grand Salon de l'Association Francaise. Bilan de l'Art Contemporain, Centre des Congrés de Quebec, Quebec

1981

Galerie Virus, Lausanne, Switzerland

Twenty Five Years of Soviet Unofficial Art: 1956-1981. Museum of Soviet Unofficial Art. Jersey City, NJ

Christmas Exhibition, Inter-Art Galerie Reich, Cologne

1981-82

Twenty Five Years of Soviet Unofficial Art: 1956-1981. Museum of Contemporary Russian Art, Montgeron, France Russian Artists from Paris. Galerie Chantepierre, Aubonne, Switzerland

1982

Religious Motifs in Soviet Unofficial Art. C.A.S.E. Museum of Russian Contemporary Art in Exile, Jersey City, NJ

The Lianozov Group. Museum of Contemporary Russian Art, Montgeron, France, C.A.S.E. Museum of Russian Contemporary Art in Exile, Jersey City, NJ

Russian Artists from Paris. Galerie de la Clé de l'Art, Geneva

Russian Painters-Paris 1971-82. Museum of Contemporary Russian Art, Montgeron, France

1982-83

The Russian Still-Life and Portrait. C.A.S.E. Museum of Contemporary Russian Art in Exile, Jersey City, NJ

Oscar Rabin, Valentina Kropivnitskaia, Alexandr Rabin. Galerie Chantepierre, Aubonne, Switzerland

1983

Unofficial Art from the Soviet Union. Cannon Rotunda and Russell Rotunda, Capitol Hill, Washington DC; with the collaboration of C.A.S.E. Museum of Contemporary Russian Art in Exile, Jersey City, NJ

The Russian Portrait, Still-Life and Landscape. Museum of Contemporary Russian art. Montgeron, France

1984

Vosstor Galerie, Goch, West Germany

Russian Expression and Surrealism Today. C.A.S.E. Museum of Contemporary Russian Art in Exile, Jersey City, NJ

Three Russians. Art Centre, Montbeliard, France

Unofficial Russian Art. Meerbuscher Kultursommer, Meerbusch, West Germany

Russians at Present. Centre Culturel de la Villedieu, Villedieu, France

Graphics Exhibition. Galerie Marie-Therese, Paris

Ten Years Ago: Tenth Anniversary of the Bulldozer Exhibition. C.A.S.E. Museum of Contemporary Russian Art in Exile, Jersey City, NJ

1989

Transit, Russian Artists between the East and West. Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, Hempstead, New York, The State Russian Museum, Leningrad

1992

Neizvestny-Rabine-Tselkov. Le Monde de L'art, Paris, France

1995

From Gulag to Glasnost. Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ; Permanent installation of The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union 1956-1986

1996

Mimi Ferzt Gallery, New York

1997

Celebrating the Still Life. Mimi Ferzt Gallery, New York

1998

A Tribute to Oscar Rabine, and Valentina Kropivnitskaia. Mimi Ferzt Gallery, New York

2004

Portraits. Mimi Ferzt Gallery, New York

2008

Intimate Diaries, Barbarian Art Gallery, Zurich

2012

Breaking the Ice: Moscow Art 1960-80s, Saatchi Gallery, London, United Kingdom

2014

Musée Maillol, Fondation Dina Vierny, Paris, France